SLAC technology designed to detect dark matter could lead to a better understanding of galaxy evolution

Sensors designed and created at SLAC could help a proposed satellite mission map the X-ray emissions of galaxies with unprecedented precision.

By Kimberly Hickok

Everyone loves a two-for-one deal – even physicists looking to tackle unanswered questions about the cosmos.

Now, scientists at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory are getting just such a twofer: particle detectors originally developed to look for dark matter are now in a position to be included aboard the Line Emission Mapper (LEM), a space-based X-ray probe mission proposed for the 2030s.

One of the primary goals of LEM is to map the X-ray emissions of galaxies with unprecedented precision in an effort to better understand galaxy formation and the history of the universe.

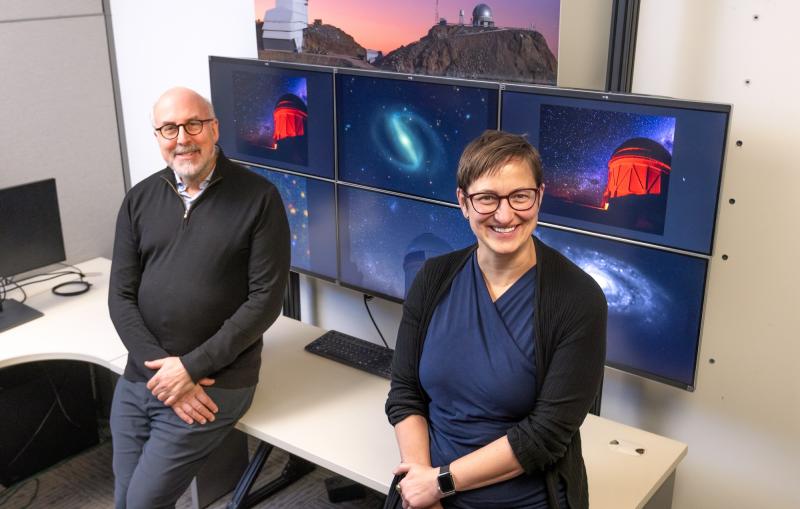

“This would be one of the few really high-resolution spectroscopy systems in space,” said Chris Kenney, senior scientist at SLAC. “From a technological perspective, X-ray spectroscopy is of great interest to SLAC. And to have our technology being used above the atmosphere is very exciting,” he said.

Tracking galactic evolution

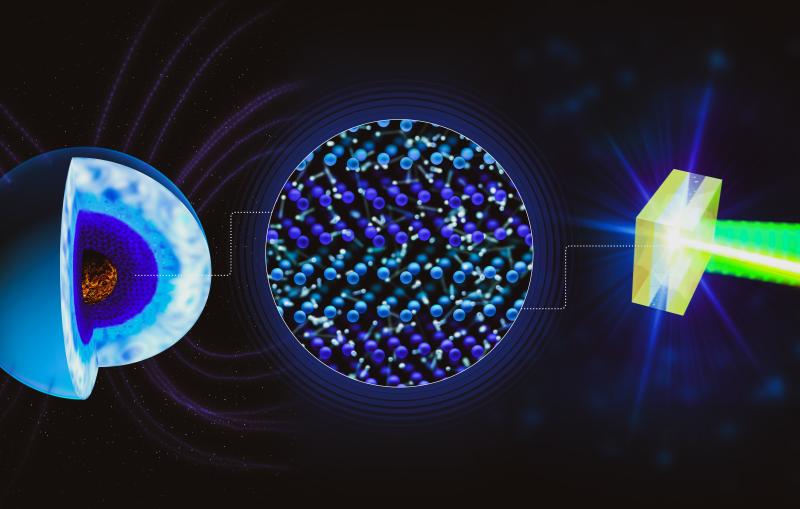

Galaxies and galaxy clusters are the largest objects in space, and understanding their evolution will help physicists get a clearer picture of the history of the universe. One way scientists may be able to map galaxy evolution is measuring X-rays coming from stars, supernovas and black holes within galaxies and their surroundings. Measuring the direction and intensity of those X-rays reveals information about the composition of the objects emitting them, and in turn, gives scientists clues about what those objects have been up to over the past tens of billions of years.

Accomplishing this requires space-based instruments capable of resolving the faintest X-ray emission lines coming from the circumgalactic medium, or the halo of gas that surrounds galaxies, and the intergalactic medium, or the plasma between galaxies. The probe also must detect X-rays coming from the Milky Way’s gas halo, but somehow filter out all other cosmic rays.

Dark matter detectors lend a hand

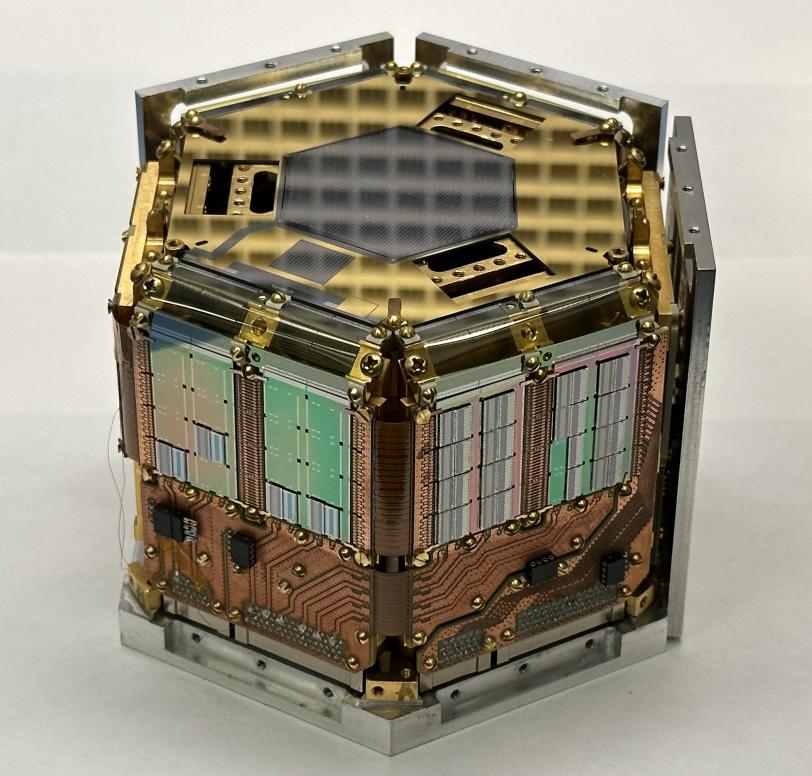

Fortunately for the LEM development team, researchers at SLAC have already created the perfect tool for the job: superconducting transition edge sensors (TES) originally designed to detect dark matter as part of the Cryogenic Dark Matter Search (CDMS).

These nanofabricated thin-film sensors are precise calorimeters that work at super cold temperatures. “We took a design that we used for a dark matter detector that's optimized for really, really good energy resolution. But it’s fairly small, so we spread it out over a much larger area to achieve the same coverage as the X-ray focal plane,” said Noah Kurinsky, a staff scientist at SLAC. Kurinsky and his colleagues at SLAC collaborated with researchers at Northwestern University in Illinois to come up with the perfect design for the repurposed TESs, which they described in a recent paper in the Journal of Astronomical Telescopes, Instruments, and Systems

Matt Cherry, a staff engineer at SLAC has been fabricating these sensors at SLAC for more than a decade, but after a recent two year hiatus from fabricating TESs, he welcomed the chance to build them again. “Because of CDMS, we have this really well-developed, well-established technology of building these sensors, and we have the processing down already,” he said. “I thought, ‘Oh this is wonderful, I would love to do this again,’ and it was exactly what they needed,” he said.

For LEM, the sensor based on Kurinsky’s design sits behind the probe’s X-ray detector and acts as a background detector, mapping energy from cosmic rays that can then be subtracted from the X-ray data. “The goal was just to tag where the cosmic ray goes within a region, but because the resolution is so good, we can actually reconstruct the location of events to the millimeter scale, which is really cool,” Kurinsky said. Without such precise cosmic ray mapping, scientists lose 15-20 percent of the data collected because the signal is indistinguishable, he explained. But the sensor SLAC built should prevent the need to eliminate any data at all.

The SLAC team shipped a few newly fabricated sensors to NASA Goddard for testing toward the end of 2023, and so far, they have far exceeded the LEM team’s expectations. “They’re thrilled,” Kurinsky said. “The LEM team gave us a list of requirements they wanted us to meet, but our sensor is already so much better than that.”

He’s optimistic that the success of these sensors and hopefully the LEM mission leads to new collaborations with future missions. “If we can demonstrate that this works really well, then it's a potential growth field for us,” Kurinsky said. “Any mission that uses TESs to do their photon detection could also easily integrate one of these.” Additionally, Kurinsky and his colleagues are exploring how stacks of these detectors could be implemented in a future space-based gamma-ray experiment.

For Cherry, helping design and fabricate an instrument he’s intimately familiar with for a new scientific goal is incredibly gratifying. “This was fun, and it turned out to be enormously helpful for someone else,” he said. “That’s something SLAC does a good job at prioritizing. We build collaborations and do projects like this because it’s interesting, and it’s worth doing.”

Citation: Stephen J. Smith et al., Journal of Astronomical Telescopes, Instruments, and Systems, 18 Oct 2023 (10.1117/1.JATIS.9.4.041005)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.